When I wrote my book Letters from the Yoga Masters, it became clear that my teacher Hari was learning multiple ways one can practice the yoga techniques. He wrote to yoga masters of various traditional lineages, asking for clarification on how they instructed a student to do specific mudras, pranayamas, asanas, meditations, mantras, etc.

Since SOYA is rooted in the practice of honouring the yoga teachings from many lineages, we have encountered abundant variations throughout the yoga practices. Are these “contradictions” intended to create doubt about the validity of the practice? Or are they simply variations based on the specific teachings that define that lineage?

Hari considered them multiple ways to practice the same technique, based on the history and success behind it. Each of the key lineages he studied with considered him a “master” due to his acquired overall skill. The variations in techniques never created doubt for him, but instead created more intrigue, awe, and respect.

I have adopted this attitude, honouring each lineage for its refinement of the techniques to support the fullness and wholeness that makes up the complete practice. For every technique, there is reasoning and science behind how it is done, and each true yoga lineage has refined this over many centuries of practice.

Let’s Review Some Variations Among Yoga Lineages:

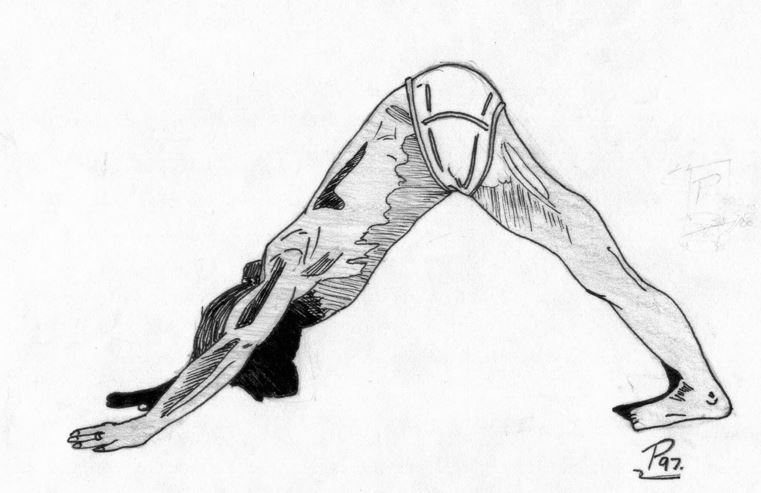

This yoga asana is commonly known by the Iyengar lineage as “Adho Mukha Svanasana”, or downward facing dog. Why? Because it mimics the stretch that a dog does when it gets up from a nap. However, in the classical teachings of yoga, this was known as “Meruasana”. Meru means “peak”, and Mount Meru is a sacred mountain in India that has 5 peaks, each one representing a different universe. Meruasana is a very sacred name for this pose, and indeed, it looks like a mountain peak! Additionally, this pose has also been called Tadasana, and Bhudharasana. Both names mean “mountain”. Most of us in the west will know Tadasana as standing upright with good posture, a foundational pose for all asanas.

“peak”, and Mount Meru is a sacred mountain in India that has 5 peaks, each one representing a different universe. Meruasana is a very sacred name for this pose, and indeed, it looks like a mountain peak! Additionally, this pose has also been called Tadasana, and Bhudharasana. Both names mean “mountain”. Most of us in the west will know Tadasana as standing upright with good posture, a foundational pose for all asanas.

Uttanasana is the name of this standing forward bend pose in the Iyengar and some other lineages, but in the Sivananda lineage this is called Padahastasana.

Uttana means “stretched out” and asana is “pose”. So this the stretched-out pose and it stretches the entire back body.

Pada means foot. Hasta means hands. So, this is the hands-to-feet pose. Both names are absolutely correct, and both are used in different lineages.

This hand mudra is used in pranayama for sealing the individual nostrils as we alternate back and forth through them. It is known as Vishnu Mudra in the Iyengar and Sivananda lineages. However, in the Gitananda lineage this particular mudra is known as Nasargha Mudra. Vishnu Mudra, as seen on the right, is from the Gitananda lineage. It is quite different, using the ring and index fingers to close the nostrils.

The hand mudras shown above are used for pranayama techniques where we breathe through one nostril at a time. Swami Vishnudevananda taught us Anuloma Viloma as a daily kriya to cleanse the nadis before doing any other pranayamas. This is from the Sivananda system. The practice is to breathe in through the right nostril and out through the left nostril, then in through the left nostril and out through the right nostril. Gradually, breath retention is increased in the practice according to the student’s ability. Anuloma means to go in the natural order, or “with the hair” and Viloma means to go against the natural order, or “against the hair”. It is intended to balance the anabolic and catabolic processes in the body while cleansing the nadis.

The manner in which we were taught this technique in the ashram is known by some in other lineages as Nadi Shodhana. A Nadi is an energy channel, and Shodhana means to purify. The purpose is to cleanse these energy channels and prepare the student for pranayama and other yogic practices. Regardless of their names, the purpose behind both pranayamas according to their lineage are to cleanse the nadis and prepare the body for the free movement of prana, the life force.

You will find further variations on these two techniques in Letters from the Yoga Masters on pages 77 and 78, including a beautiful technique of Nadi Shodhana as taught by Swami Yogeshwaranand.

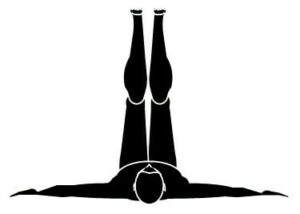

There are “full body” mudras explained in the Hatha Yoga Pradipika. They are powerful and more advanced for those who have developed their practices to where they are stable and comfortable in asana and pranayama. One important mudra is Viparita Karani. In the Iyengar system, this mudra is often presented as a modified version of the shoulderstand and is simply resting the legs up the wall. It is a very useful modification for people who are not able to do the shoulderstand, and allows them to participate fully in an asana class. However, the power behind the actual mudra Viparita Karani is quite different.

There are “full body” mudras explained in the Hatha Yoga Pradipika. They are powerful and more advanced for those who have developed their practices to where they are stable and comfortable in asana and pranayama. One important mudra is Viparita Karani. In the Iyengar system, this mudra is often presented as a modified version of the shoulderstand and is simply resting the legs up the wall. It is a very useful modification for people who are not able to do the shoulderstand, and allows them to participate fully in an asana class. However, the power behind the actual mudra Viparita Karani is quite different.

Viparita means “reverse” and Karani means “doing”. This mudra is intended to reverse the flow of the soma nectar back to its origin at the bindu chakra. There is a whole explanation of this in the Hatha Yoga Pradipika. Additionally, you will find information in Letters from the Yoga Masters on pages 124-125. Indu Arora also beautifully explains the differences between these two postures here.

Conclusion

I do not consider the inconsistency of “names” for techniques to be as important as the intent behind the technique according to the lineage. You can see by what I have shared that there is energy in a name, and the classical techniques have been named to represent their energetic purpose. Different lineages name techniques differently to suit their intent. While investigating classical yoga books, there are endless descriptions of similar techniques with different names. As a practitioner of yoga who follows many paths, I cannot resolve this, nor do I feel a need to. This is the conundrum of studying many paths in one lifetime. It is much simpler to just follow one path. It is also much narrower. Swami Sivananda and Hari are two examples of yoga masters who could not limit themselves to one path, but rather dove into them all with absolute glee!

What I do know is what I have been trained in by my classical teachers – the most significant being Dr. Hari Dickman, Swami Vishnudevananda, Namadeva Acharya, Erich Schiffmann, and Dr Ananda Balayogi Bhavanani. I am so grateful for the opportunity to have been exposed to many lineages and encounter these practices through various names and forms.

This is the world of yoga with its many classical lineages. We are blessed with wonderful opportunities to learn from them all. The paths are many, the Truth is One. I respect these traditional paths and I appreciate deeply the conviction from great teachers wishing that their techniques are passed on and done correctly.

I am very certain we will never find agreement on the names given to various yoga techniques across all lineages. However, if you are a teacher, then teach your students that there are variations and differences, so that your students have confidence in what they are learning as they are exposed to great teachings. The classical teachings of yoga are rich and full and abundant with centuries of refinement, all for our benefit.

Images are provided from Thor Polukoshko, Mugs McConnell, and Yogafont.

Marion Mugs McConnell is the co-founder of SOYA and the SOYA Yoga Teacher Training program. This year she celebrates 51 years of yoga and continues to dedicate her life to this amazing path, revealing the gems of true, classical yoga.

Mugs is the author of Letters from the Yoga Masters: Teachings Revealed through Correspondence from Paramhansa Yogananda, Ramana Maharshi, Swami Sivananda, and Others, published by North Atlantic Books copyright © 2016 ISBN 978-1-62317-035-6.

Recent Comments